Where Spring Comes on like a Thunderclap!

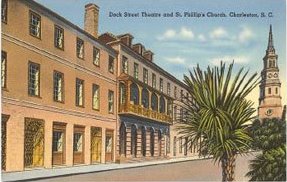

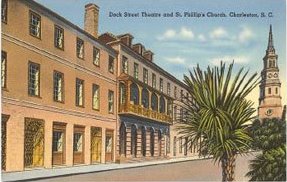

I am entering a magazine article by Albert Goldman for many reasons but also for what happened in Charleston after the article was printed and how it affected my perspective of who I was, who my father was and where I was growing up. I was only 11 during the Thanksgiving of 1972 when my father, sister and I gave Albert Goldman directions while he was walking down Church Street in Charleston. My fathers office was also on Church Street and my sister and I were playing outside while we waited for our father. Dad's office was close to the Dock Street Theater and St. Philips Church. (see postcard below)

I am copying the article Mr. Goldman wrote about Charleston: Where Spring Comes On Like a Thunderclap! from Travel and Leisure magazine of February/March 1973 as he mentions running into us and spending time with my father. My father was impressed by Albert Goldman. How often did one meet writers who had just completed a book called Lenny Bruce and another called Freakshow about rock and roll. Mr. Goldman was also the music editor for Life magazine and also contributed articles in High Times a magazine about the marijuana "lifestyle." My father was so fascinated by this man that he invited him to our house for Thanksgiving and took him out the next evening for dinner at Henry's.

Of course when this article was written it caused an unbelieveable stir in Charleston as many did not travel south and write about it in such a prominent magazine. Many months after the article was written many Charlestonians thought that the Jewish writer from New York was asked to Thanksgiving dinner at the home of - well, let's say, a more prominent local family. People thought this as there was a family with two young daughters living in the vicinity where Goldman asked for directions. (and I do know the family is as well as their daughters.) Later, my father, in a brusque manner, informed those who asked, “What blueblood would invite a Yankee from New York to his home for dinner?! It was not _____ ______, but it was me!”

Where Spring Comes On Like a Thunderclap!

Oh, how I hate New York in winter! I can take it up to Christmas. After that, I start to die. I rarely venture out of doors. I cling to the comforts of home. If I'm compelled to emerge from my steam-heated, rotary-vaporized, cloth-hung retreat, I insulate myself in fur, wool and rubber, like a diver preparing to commit himself to a gray, sullen sea. Once out in the streets, where the raw wind whips the steam off he manholes in crazy wraiths, I imagine myself the schlemiel in some dreary Slavic novel. Bent double in a long coat, turtle necked inside a high collar, fearing flu and feeling my soul separating from my body, I ache for spring.

Spring! The lost season. Where has it gone? Some people seek it in the tropics. What they find is eternal summer. A burning sun, a stupefying heat, a dopey bliss that dissolves the mind. What I crave is the assurance of revival. Not just the re-awakening of nature, but the revitalization of man. Remember the first lines of Chaucer's pilgrimage, where he ranges up the scale of being from wind and water to birds and beasts to find the highest stirring of the season in men and their grateful sense of God? That's what I desire—that genial, that exhilarating sense of universal renascence. Where do I find it? Where else, but in the American Southland. In a gracious old city like Charleston, South Carolina, where the beauties of nature blend with the arts of man in a harmony that lies like balm on a northerner's exacerbated soul.

When you alight at Charleston, you must put up an inn that would have reminded Chaucer of his Italian journeys. The Mills Hyatt House (today, in 2006, known as the Mills House) is its name. The “open sesame!” to the whole Charleston experience, this hostelry symbolizes the delicate balance that has been struck in the city between its priceless heritage of architecture, interior decor, gardening, cooking and fine manners and the exigencies of contemporary living, which demand three-story parking lots and push-button elevators. In any other city the quixotic, project of tearing down a handsome but hopelessly dilapidated hotel built in 1853 and building it up from the ground would have certainly come to grief.

The impulse to fill the fine old shell with pseudo-antiques, jiffy-boy snack bars and silly curio shops would have proven irresistible. Charleston rebuffs such vulgarities with the easy condescension of a Tradd Street dame confronting an antique dealer from Brooklyn Heights. Flawless in every detail, the Mills House is the loveliest and most gracious hotel I know in America. From the moment you step inside its intimately proportioned vestibule, suggestive more of a handsomely appointed mansion than a 250-room hotel, you begin to feel the deep peace and contentment of the city. Like a perfect note from a tuning fork, the Mills house sets the tone for Charleston.

When you step out the door into Meeting Street, you catch the next lovely note, tolling down from the mellow bell of St. Michael's, whose soaring 18th-century steeple is still the highest point in this city, so miraculously free of high-rises and low urban sprawl. A stroll down Meeting Street is a sally into American history. As you advance block-by-block—along this handsome, umbrageous avenue fragrant with the odor of blossoms and rejoicing with the song of birds, you hold your breath, fearing the violation of the illusion. There is nothing to fear, however. With a jealousy like the dragon Fafner guarding the Rheingold, Charlestonians have dedicated their lives and fortunes to preserving intact their heritage. Indeed, through an unparalleled program of urban conservation and restoration, they have extended far and wide the boundaries of their historical district, until today they present you with two pictures, one an engraving of Charleston in 1851, the other a photograph from 1970—and defy you to find a difference!

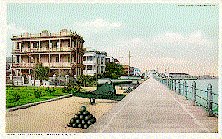

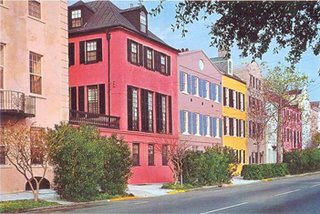

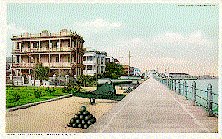

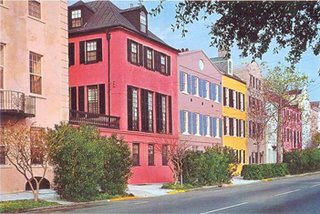

Like a mirage the prospect extends before you, house after delicately carved house, crammed side by side, like yachts moored at dock, each finely columned veranda turned shyly away from the street, each narrow facade embellished with wrought iron, crowned with the stone pineapple of hospitality and highlighted with glancing reflections from fine old brasswork and fan-shaped windows. Peeking occasionally across a garden wall into some miniature Versailles, replete with milled gravel paths, topiary trees and nude boys pouring water, you complete a leisurely progress to the Battery. Here an Old World maritime promenade opens out to greet you. Giant oaks bestride the park, trailing gray Spanish moss, old cannon point out toward Fort Sumter and a magnificent file of planters’ mansions rear their stately neo-classic porticoes toward the favored southeastern exposure. By the time you've mounted the seawall and started to walk by the brightly tinted houses along Rainbow Row, you've stepped out of time and into the serenity of an urban eternity.

So quiet and reserved is the life of Charleston that the city often appears to be asleep. On my first visit, on a Thanksgiving Day, I walked for upwards of an hour without seeing a soul. Then, meandering down Church Street, past the Dock Street Theater, site of the “first theater in the New World” — everything in Charleston is a “first” — I noticed a man shepherding two little girls, obviously his daughters. He asked me weather I was enjoying the city, and when I replied with enthusiasm, he insisted I get in his car and go for a tour of the town, He wound up his delightful recital of local history, archeology and gossip with a generous invitation to join him and his wife for Thanksgiving dinner. (He ducked into his office and phoned the lady while I was imagining what it would be like to buy an antebellum mansion for $40,000 and restore it to its original splendor.)

Not content on feasting me for the holiday, he insisted on taking me the next day to lunch at Henry's, a dusky old bar across from the marketplace, where I made my first acquaintance with those delicious local dishes: she-crab soup, Bulls bay oysters, red rice and that pungent spreading cheese that Charlestonians always serve with drinks.

In the spring, Charleston's hospitality is organized. A whole series of tours are offered expressly for visitors. Capitalizing on the magic that darkness works in this city where old cobblestone streets are lined with gas lamps and the ringing of boot heels resounds through the still night air with a steady drumming– the ever-busy Historic Charleston Foundation escorts you by candlelight up and down the city's most picturesque blocks. Attractive young women in long gowns lead you along secluded garden walks and into charming little homes that housed 19-century artisans. They show you the family's cherished silver plate, its locally carved furniture and ancestral portraits. What the women, old and young, who conduct these tours seem to be saying is that there is no pleasure equal to the Dickensian delight of making yourself as snug and cozy as a pretty bird inside its nest. Domesticity—you cheery god! Where else have you such adoring devotees!

The charm of Charleston's tiny baked-brick artisan houses is balanced by the grandeur of the great plantations that lie outside the city on the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. Middleton Place, a half hour drive along scenic Highway 61, is the grandest of these estates, being nothing less than a direct translation of the landscape artistry of the Tuileries Gardens and Versailles to a rice plantation in the Carolinas.

A disciple of the great Le Notre laid out this noble plan. To feel the force of his original inspiration, you have to imagine yourself landing at the waterside in a barge and casting your eyes over a cast carpet of immaculate lawn laid around two symmetrical ponds, shaped and balanced like the wings of a butterfly, before mounting up a succession of finely molded terraces that lead the eye to the crest of the hill, where a huge tripartite mansion once commended the prospect with regal authority.

Today, only one wing of the mansion remains; but inside that ample fragment, the new masters of Middleton–an engagingly youthful couple named Charles and Carol Duell–labor tirelessly to restore the estate to its original splendor. Under their aegis, Middleton Place–recently designated a registered national historic landmark–has been revived as a replica of a traditional plantation, complete down to the beautiful maiden who combs and spins the wool of the estate's grazing sheep.

Magnolia Gardens, down the road from Middleton Place, transports you into an entirely different world. Rich, mazy and romantic where Middleton is sculpted, geometric and classical, Magnolia is the last word in the nature-worshipping “English garden” of the late 18th century. John Galsworthy, of the great English novelist, whose principal passion was gardening, was overwhelmed by the bounty of Magnolia. “Nothing so free and gracious,” he rhapsodized, “so lovely wistful, so richly colored, yet so ghost-like exists…It is a kind of Paradise…a miraculously enchanted wilderness.” Yet, astonishingly, the environs of Charleston contain an even more enchanting landscape, titled Cypress Gardens.

Here you glide in a gondola through a forest of towering cypresses—strange trees that “breathe” through knobby brown roots thrust up like periscopes from the bottom of the swamp—gazing raptly at the black glass surface of the water, where you behold a sunken forest quivering in sinister ripples. Edgar Allan Poe is the presiding genius, mourning in his Ulalume “down by the dank tarn of Auber, in the ghoul haunted woodland of Weir.”

One last note about spring in the South. It rains there! If you’re a fancier of deep, steady self-enclosing rain as I am, you’ll be content to sit indoors gazing out at the downpour–or even sitting inside a car feeling the isolation of the deluge. The “shoures soote”–Chaucer’s “sweet showers”–fall sporadically all through the months of March and April on our fecund southland. So be prepared for this drench of fertility. Let it rain, let it pour. Look at it, look through it, brood in its misty dimness. When these precipitate showers have “perced to the roote,”the most beautiful landscape in our country will turn vernal green and embrace humankind with flowers.

I am copying the article Mr. Goldman wrote about Charleston: Where Spring Comes On Like a Thunderclap! from Travel and Leisure magazine of February/March 1973 as he mentions running into us and spending time with my father. My father was impressed by Albert Goldman. How often did one meet writers who had just completed a book called Lenny Bruce and another called Freakshow about rock and roll. Mr. Goldman was also the music editor for Life magazine and also contributed articles in High Times a magazine about the marijuana "lifestyle." My father was so fascinated by this man that he invited him to our house for Thanksgiving and took him out the next evening for dinner at Henry's.

Of course when this article was written it caused an unbelieveable stir in Charleston as many did not travel south and write about it in such a prominent magazine. Many months after the article was written many Charlestonians thought that the Jewish writer from New York was asked to Thanksgiving dinner at the home of - well, let's say, a more prominent local family. People thought this as there was a family with two young daughters living in the vicinity where Goldman asked for directions. (and I do know the family is as well as their daughters.) Later, my father, in a brusque manner, informed those who asked, “What blueblood would invite a Yankee from New York to his home for dinner?! It was not _____ ______, but it was me!”

Where Spring Comes On Like a Thunderclap!

Oh, how I hate New York in winter! I can take it up to Christmas. After that, I start to die. I rarely venture out of doors. I cling to the comforts of home. If I'm compelled to emerge from my steam-heated, rotary-vaporized, cloth-hung retreat, I insulate myself in fur, wool and rubber, like a diver preparing to commit himself to a gray, sullen sea. Once out in the streets, where the raw wind whips the steam off he manholes in crazy wraiths, I imagine myself the schlemiel in some dreary Slavic novel. Bent double in a long coat, turtle necked inside a high collar, fearing flu and feeling my soul separating from my body, I ache for spring.

Spring! The lost season. Where has it gone? Some people seek it in the tropics. What they find is eternal summer. A burning sun, a stupefying heat, a dopey bliss that dissolves the mind. What I crave is the assurance of revival. Not just the re-awakening of nature, but the revitalization of man. Remember the first lines of Chaucer's pilgrimage, where he ranges up the scale of being from wind and water to birds and beasts to find the highest stirring of the season in men and their grateful sense of God? That's what I desire—that genial, that exhilarating sense of universal renascence. Where do I find it? Where else, but in the American Southland. In a gracious old city like Charleston, South Carolina, where the beauties of nature blend with the arts of man in a harmony that lies like balm on a northerner's exacerbated soul.

When you alight at Charleston, you must put up an inn that would have reminded Chaucer of his Italian journeys. The Mills Hyatt House (today, in 2006, known as the Mills House) is its name. The “open sesame!” to the whole Charleston experience, this hostelry symbolizes the delicate balance that has been struck in the city between its priceless heritage of architecture, interior decor, gardening, cooking and fine manners and the exigencies of contemporary living, which demand three-story parking lots and push-button elevators. In any other city the quixotic, project of tearing down a handsome but hopelessly dilapidated hotel built in 1853 and building it up from the ground would have certainly come to grief.

The impulse to fill the fine old shell with pseudo-antiques, jiffy-boy snack bars and silly curio shops would have proven irresistible. Charleston rebuffs such vulgarities with the easy condescension of a Tradd Street dame confronting an antique dealer from Brooklyn Heights. Flawless in every detail, the Mills House is the loveliest and most gracious hotel I know in America. From the moment you step inside its intimately proportioned vestibule, suggestive more of a handsomely appointed mansion than a 250-room hotel, you begin to feel the deep peace and contentment of the city. Like a perfect note from a tuning fork, the Mills house sets the tone for Charleston.

When you step out the door into Meeting Street, you catch the next lovely note, tolling down from the mellow bell of St. Michael's, whose soaring 18th-century steeple is still the highest point in this city, so miraculously free of high-rises and low urban sprawl. A stroll down Meeting Street is a sally into American history. As you advance block-by-block—along this handsome, umbrageous avenue fragrant with the odor of blossoms and rejoicing with the song of birds, you hold your breath, fearing the violation of the illusion. There is nothing to fear, however. With a jealousy like the dragon Fafner guarding the Rheingold, Charlestonians have dedicated their lives and fortunes to preserving intact their heritage. Indeed, through an unparalleled program of urban conservation and restoration, they have extended far and wide the boundaries of their historical district, until today they present you with two pictures, one an engraving of Charleston in 1851, the other a photograph from 1970—and defy you to find a difference!

Like a mirage the prospect extends before you, house after delicately carved house, crammed side by side, like yachts moored at dock, each finely columned veranda turned shyly away from the street, each narrow facade embellished with wrought iron, crowned with the stone pineapple of hospitality and highlighted with glancing reflections from fine old brasswork and fan-shaped windows. Peeking occasionally across a garden wall into some miniature Versailles, replete with milled gravel paths, topiary trees and nude boys pouring water, you complete a leisurely progress to the Battery. Here an Old World maritime promenade opens out to greet you. Giant oaks bestride the park, trailing gray Spanish moss, old cannon point out toward Fort Sumter and a magnificent file of planters’ mansions rear their stately neo-classic porticoes toward the favored southeastern exposure. By the time you've mounted the seawall and started to walk by the brightly tinted houses along Rainbow Row, you've stepped out of time and into the serenity of an urban eternity.

So quiet and reserved is the life of Charleston that the city often appears to be asleep. On my first visit, on a Thanksgiving Day, I walked for upwards of an hour without seeing a soul. Then, meandering down Church Street, past the Dock Street Theater, site of the “first theater in the New World” — everything in Charleston is a “first” — I noticed a man shepherding two little girls, obviously his daughters. He asked me weather I was enjoying the city, and when I replied with enthusiasm, he insisted I get in his car and go for a tour of the town, He wound up his delightful recital of local history, archeology and gossip with a generous invitation to join him and his wife for Thanksgiving dinner. (He ducked into his office and phoned the lady while I was imagining what it would be like to buy an antebellum mansion for $40,000 and restore it to its original splendor.)

Not content on feasting me for the holiday, he insisted on taking me the next day to lunch at Henry's, a dusky old bar across from the marketplace, where I made my first acquaintance with those delicious local dishes: she-crab soup, Bulls bay oysters, red rice and that pungent spreading cheese that Charlestonians always serve with drinks.

In the spring, Charleston's hospitality is organized. A whole series of tours are offered expressly for visitors. Capitalizing on the magic that darkness works in this city where old cobblestone streets are lined with gas lamps and the ringing of boot heels resounds through the still night air with a steady drumming– the ever-busy Historic Charleston Foundation escorts you by candlelight up and down the city's most picturesque blocks. Attractive young women in long gowns lead you along secluded garden walks and into charming little homes that housed 19-century artisans. They show you the family's cherished silver plate, its locally carved furniture and ancestral portraits. What the women, old and young, who conduct these tours seem to be saying is that there is no pleasure equal to the Dickensian delight of making yourself as snug and cozy as a pretty bird inside its nest. Domesticity—you cheery god! Where else have you such adoring devotees!

The charm of Charleston's tiny baked-brick artisan houses is balanced by the grandeur of the great plantations that lie outside the city on the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. Middleton Place, a half hour drive along scenic Highway 61, is the grandest of these estates, being nothing less than a direct translation of the landscape artistry of the Tuileries Gardens and Versailles to a rice plantation in the Carolinas.

A disciple of the great Le Notre laid out this noble plan. To feel the force of his original inspiration, you have to imagine yourself landing at the waterside in a barge and casting your eyes over a cast carpet of immaculate lawn laid around two symmetrical ponds, shaped and balanced like the wings of a butterfly, before mounting up a succession of finely molded terraces that lead the eye to the crest of the hill, where a huge tripartite mansion once commended the prospect with regal authority.

Today, only one wing of the mansion remains; but inside that ample fragment, the new masters of Middleton–an engagingly youthful couple named Charles and Carol Duell–labor tirelessly to restore the estate to its original splendor. Under their aegis, Middleton Place–recently designated a registered national historic landmark–has been revived as a replica of a traditional plantation, complete down to the beautiful maiden who combs and spins the wool of the estate's grazing sheep.

Magnolia Gardens, down the road from Middleton Place, transports you into an entirely different world. Rich, mazy and romantic where Middleton is sculpted, geometric and classical, Magnolia is the last word in the nature-worshipping “English garden” of the late 18th century. John Galsworthy, of the great English novelist, whose principal passion was gardening, was overwhelmed by the bounty of Magnolia. “Nothing so free and gracious,” he rhapsodized, “so lovely wistful, so richly colored, yet so ghost-like exists…It is a kind of Paradise…a miraculously enchanted wilderness.” Yet, astonishingly, the environs of Charleston contain an even more enchanting landscape, titled Cypress Gardens.

Here you glide in a gondola through a forest of towering cypresses—strange trees that “breathe” through knobby brown roots thrust up like periscopes from the bottom of the swamp—gazing raptly at the black glass surface of the water, where you behold a sunken forest quivering in sinister ripples. Edgar Allan Poe is the presiding genius, mourning in his Ulalume “down by the dank tarn of Auber, in the ghoul haunted woodland of Weir.”

One last note about spring in the South. It rains there! If you’re a fancier of deep, steady self-enclosing rain as I am, you’ll be content to sit indoors gazing out at the downpour–or even sitting inside a car feeling the isolation of the deluge. The “shoures soote”–Chaucer’s “sweet showers”–fall sporadically all through the months of March and April on our fecund southland. So be prepared for this drench of fertility. Let it rain, let it pour. Look at it, look through it, brood in its misty dimness. When these precipitate showers have “perced to the roote,”the most beautiful landscape in our country will turn vernal green and embrace humankind with flowers.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home